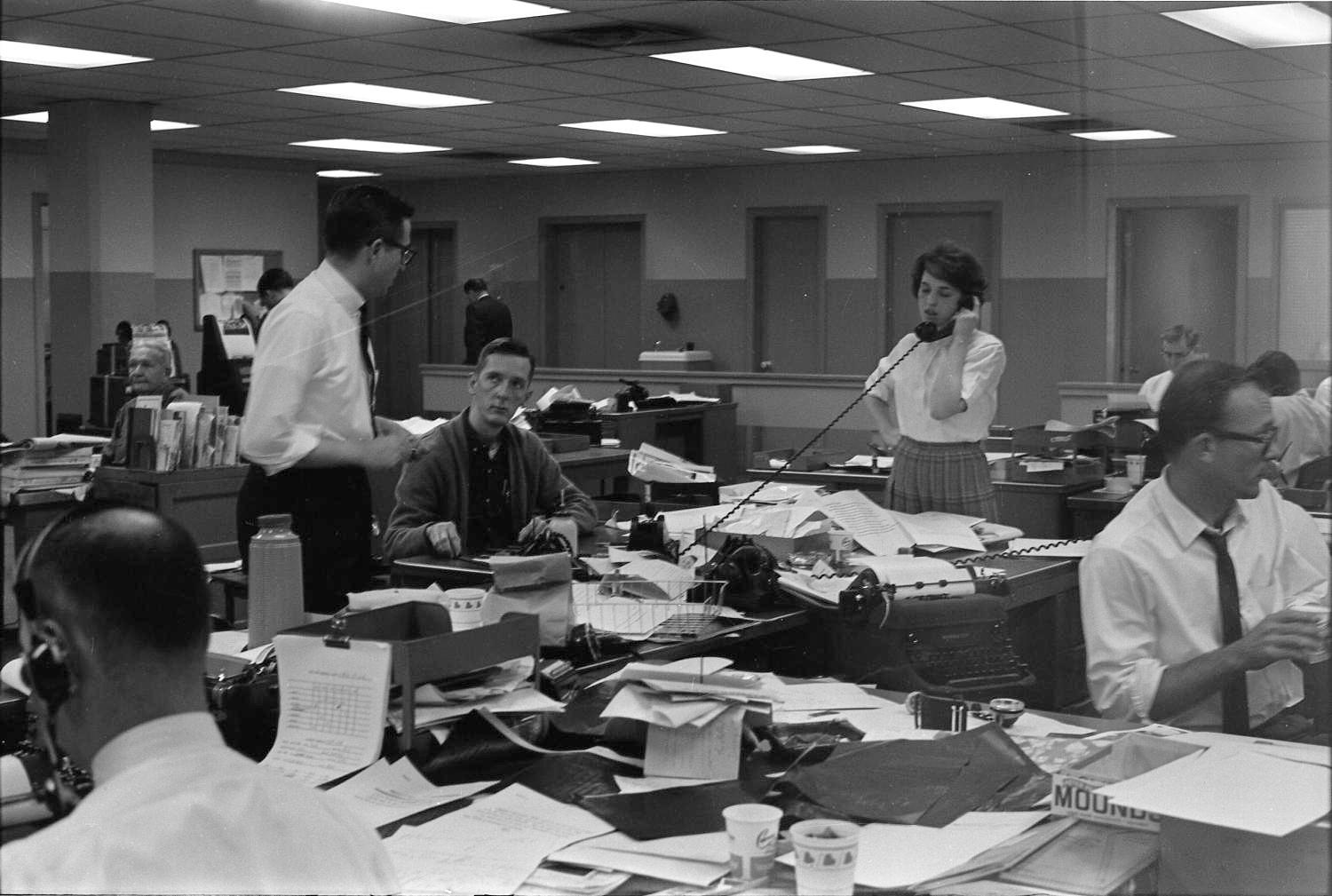

What was a small newspaper office like half a century or longer ago, in the era of “hot type” generated by huge, complex Linotype machines? I’ll tell you.

The Daily News-Telegram then was housed on Main Street in Sulphur Springs, Tex., (population 9,160 in 1960) one block away from the town’s square. The company leased three storefronts, only one of them with an unlocked door. The public entrance opened to an office with a counter, behind which were the desks of managing editor Joe Woosley, society editor Christine Moelk, the local reporter and sports editor (me, starting in 1960), head clerk and proof reader Nadine Greer, and bookkeeper Elbert Wilkins. My dad, the editor and publisher, occupied an alcove directly behind the front office. (It had no door, and Pop welcomed anyone who walked in,. no matter how tedious or boring they may be.)

Headed back from the front office and that of my father, you entered a nether world that would stun anyone born after 1970—a complex manufacturing operation that on the hottest summer days felt like a scene from hell.

Aligned along the right side were four Linotype machines. Learn all about them on Wikipedia, but they worked like this: An operator at a keyboard typed in a story. Each keystroke brought a matrice of the letter or number into a form. When the narrative filled a line, the Linotype operator would insert a hyphen or a spacer if necessary to make the line justify both left and right. Then the line would be encased in molten medal, which quickly cooled and was shot into a tray behind the previous line of type that had been typeset. At the back of every Linotype machine was a fire that melted the bars of metal (composed mainly of lead).

In my experience Linotype operators were pretty learned people—smart, educated, and interested in the stories they were typesetting. That would certainly describe Jeff Campbell, William Hutchins, and Wilma Anonette, first-rate people who ran the first, second, and third Linotype machines for many years. But at the end of the row was Sam. I cannot remember Sam’s last name, which is just as well because nobody spoke very well of him.

Middle-aged, Sam seemed intensely unhappy, and had no family that we knew of. He spoke only when spoken to. All of that his coworkers could live with. What was harder to understand was Sam’s seeming lack of attention to what he was doing. Words would be reversed. Misspellings were rampant. Entire lines or even paragraphs would be left out. Nadine Greer, who proof read all of the wire service stories, forever complained about Sam, and no doubt begged my dad to fire him. Even I suggested as much.

But Bill Frailey valued loyalty, and in any event had no stomach for firing anyone who wasn’t caught stealing money from the safe or threatening other employees. So Sam stayed, year after year, and Nadine kept complaining. Then one noon when I was away at college, Sam got up from his machine to go to lunch and never came back or explained why or gave his resignation.

Most back-shop employees in that era were Daily News-Telegram lifers. Guy Felton, foreman of the back shop, was such a person. Among his duties was to assemble type and other elements of advertisements. Our two pressmen were lifers as well. Robert Irons doubled as boss of our little stereotyping department. There the comics, certain national advertisements, photographs and so forth were turned into plates which were then placed in the metal frames of pages, called “chases.” Robert also melted the type from previous editions to make the metal bars which were fed to the Linotype machines.

Willard, the other pressman, doubled as assembler of the actual pages of the newspaper. In other words, he was the one who took the headlines and typeset stories and ads and photos and actually placed them in the chase. An important part of that task was to make sure the hundreds of pieces of type inside the chase were snug and completely tightened down. That’s because Willard had to lift the chase containing the completed page, probably weighing more than 100 pounds, to a cart and then from the cart to the flatbed press. Imagine the page falling apart as it was lifted! Willard always carefully tested each chase before lifting it, and occasionally had to insert leading to secure loose lines of type. We always joked about Willard’s dropping a chase, causing it to splatter across the floor. But of course that never happened.

To the left of the composing room, at the back of the second storefront, was the press room. Our press was ancient, able to print only eight pages at a time. On days that required more than eight pages, a second press room would start at about noon. I believe the output of this press was about 3,000 copies an hour, so a press run took a bit longer than an hour. The simplicity and relatively slow speed of the press no doubt had something to do with the fact that it lasted long past a normal life cycle.

I should mention that my father also published a second newspaper, the weekly Hopkins County Echo. Almost nobody inside the city of Sulphur Springs read it or even knew it existed. It circulated almost entirely to rural residents of Hopkins County, as well as to former residents. The Echo must have made us a lot of money in its day. That’s because it had little if any editorial or typesetting costs. Rather, it was filled with local stories from the previous week’s News-Telegram. The Hopkins County Echo was printed on Thursdays for mail delivery the next day, and always required at least two press runs.

When my father bought Echo Publishing Company in 1951, in partnership with his cousin Kenneth Kraft, the Echo had by far the larger circulation—I’m thinking about 5,000, versus the Daily News-Telegram’s 1,700. Gradually the News-Telegram added readers and the Echo lost them. The last Hopkins County Echo was published about 2015. By then its readership was down to barely more than 100.

A big component of Echo Publishing was commercial printing, which occupied most of the space behind the second storefront. We were the third-largest supplier of tags and other printed form to Texas cotton gins. I got my start at age 14 in this department. Eventually I was promoted to pressman, and one eventful day I managed to disable three of the four presses. Perhaps that’s why Pop soon thereafter made me his cub reporter, to save his commercial printing business from my destructive acts.

The last storefront held the advertising department. It was staffed largely by Elwood Highfield, Mun Watkins, and Cody Greer (Nadine’s husband), Cody doubling as the newspaper’s photographer.

This was my little word of newspapers, circa 1960. I’ll describe how we put out an edition in a future blog.

On Thursday, August 12, 1954, the front page of the Daily News-Telegram contained a photograph quite unlike any I had seen, before or since. It was a two-column facial photo of a dead man, his head on a pillow inside a casket, his body covered by a blanket below the neck. My father agreed to publish the photograph at the request of police, whose attempt to identify the dead man had proved futile. Maybe a News-Telegram reader would recognize him.

On Thursday, August 12, 1954, the front page of the Daily News-Telegram contained a photograph quite unlike any I had seen, before or since. It was a two-column facial photo of a dead man, his head on a pillow inside a casket, his body covered by a blanket below the neck. My father agreed to publish the photograph at the request of police, whose attempt to identify the dead man had proved futile. Maybe a News-Telegram reader would recognize him. Here is what we know: Thomas Gregory, 17 years old, was driving his Ford to his family’s farm house four miles west of Sulphur Springs. His dad Judson Gregory, 45, a dairy farmer, was in the front passenger seat. Two of Judson Gregory’s grandsons, Douglas McCord and Mark Gregory, both age 2, occupied the back seat. Thomas Gregory steered the car off State Highway 11 onto the dirt road going to his home and drove it up the short ramp leading to the Cotton Belt Route railway tracks. At the apex, with the Ford centered on the tracks, the car inexplicably stopped. The time was 2:55 p.m., four days before Christmas in 1961.

Here is what we know: Thomas Gregory, 17 years old, was driving his Ford to his family’s farm house four miles west of Sulphur Springs. His dad Judson Gregory, 45, a dairy farmer, was in the front passenger seat. Two of Judson Gregory’s grandsons, Douglas McCord and Mark Gregory, both age 2, occupied the back seat. Thomas Gregory steered the car off State Highway 11 onto the dirt road going to his home and drove it up the short ramp leading to the Cotton Belt Route railway tracks. At the apex, with the Ford centered on the tracks, the car inexplicably stopped. The time was 2:55 p.m., four days before Christmas in 1961.