It was no accident that my first byline in the Dallas Times Herald during the summer of 1965, on June 24, was about railroads. What do you do with interns? You throw them little stories for the longest time, is what. Thus I was, with Ruth Ayres, the every-other-day obituary writer. If I wanted to break out of that routine, I’d have to suggest my own story to be set loose on, and so I did, and by necessity it was about something I knew a little bit about.

The Southwest Railroad Historical Society, based in Dallas, and its 125 members had just acquired three steam locomotives to add to the two already on exhibit at Fair Park, home of the Texas State Fair. SRHS was negotiating to acquire even more. But first the members had to figure out how to get those three teakettles (one of them actually a huge locomotive more than 100 feet long, which Union Pacific had named Big Boy) from where they were stored to Fair Park, a mile away. Would they need to lay track? All this was fodder for a feature story I suggested to the city editor, Ken Smart, and he said go to it.

A steam locomotive, I wrote, is “almost as rare as a whooping crane—the difference is that the crane can reproduce.” By 1965, these magnificent black machines were all but gone from the railroad scene, replaced by diesel-fed locomotives that all looked the same underneath their paint. I see in rereading the piece that I spoke to Dean Hale, a vice president of the society and a writer for a trade magazine. I would get to know Dean later in my life as one of those people who are always going to do some great thing but never get around to doing it. And by the way, I was still in Dallas on August 22 to report that the three steamers finally made it to Fair Park.

The next week, I came back to the railroad beat I seemed to be creating. The Katy Railroad, which ran between Kansas City and Dallas (among other places), thought it had permission to take off its last two passenger trains, the Texas Special and Katy Flyer, due to losses they incurred. My idea was to write a feature story about the trains to appear the day of their last departures, and to ride the last Texas Special out of Kansas City into Dallas the following morning as a followup story.

But on June 30, the day of the last departures, the Interstate Commerce Commission ordered both trains continued another four months while the federal agency held hearings on the matter. Nothing doing, responded Katy’s new president, John W. Barriger. The ICC order came 11 hours before the last departure, he said, and the law requires 10 days’ notice. The spat turned my soft feature story into a nice 18-paragraph news story.

That night I took the last northbound Texas Special to Denison, Tex., about 120 miles, and the morning of July 1 rode the final southbound version of the train. Delayed meeting freight trains in Oklahoma, it left Denison two hours late—too late, in fact, for my story about the last run to appear in that afternoon’s paper. It had to wait for the next day’s editions. But I scored my second byline.

With that, having shown some initiative and proved I could follow through with publishable stories, I started getting better assignments. A big bank robbery prompted Smart to have me write about how banks protect themselves. The resulting story was not a world-stopper, but it is fun to reread. “There’s little to stop a would-be bandit from attempting or even carrying through a robbery,” I wrote. “Only after the criminal has actually gotten a bank’s money does the many-faceted operation of capture begin. That’s when a bandit gets in trouble.” That ran on July 14.

Four days later, I was back on the railroad beat with a feature about Dallas Union Terminal. “Late every afternoon,” I wrote, “when jet airliners are arriving every few minutes at Love Field, the large, marble lobby of Union Terminal becomes all the more conspicuous for its emptiness. As they have for 49 years, passenger trains still arrive and depart beneath the trainsheds. But they’re fewer and far less glamorous than the trains of past years. Inside the station, tiny lines form at the two ticket windows. The patrons are now mostly older people. People buy their tickets and then either sit in the two rows of wooden benches or buy something to eat inside the small glass-enclosed lunchroom. Dining cars are getting scarce. Upstairs, above the twin escalators which haven’t run for 13 years, the old, high-ceiling waiting room with its golden chandeliers, and the large original lunchroom, are dusty and bare.”

This is really one of the earliest feature stories I wrote that I can look back upon with a bit of pride. I was learning how to tell a story well.

The Times Herald was an afternoon newspaper six days a week, then published its big Sunday morning edition. Most of that summer I was assigned to work Saturdays, from 2 to 10 p.m. The first three hours most Saturdays were spent at Dallas police headquarters, made famous on November 24, 1963, when nightclub owner Jack Ruby shot president John Kennedy’s accused assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, to death.

It’s rather terrifying as a reporter to walk into a place like this not knowing the first thing about who to talk to and how to find things out. Fortunately, a Dallas Morning News reporter scarcely older than me showed up my first Saturday and took pity, explaining the routines. For instance, every incident report was typed up in multiple copies, and one of them was quickly placed in the press room for reporters to read. And we listened to the police radios above our desks, although listening to them was one thing but understanding a thing that was said in policespeak quite another. Despite all my Saturdays spent at police headquarters, I don’t recall any crime of consequence occurring. The regular night reporter who came in at 5 o’clock was kept far busier as the evening hours passed.

At 5, I’d go to the Times Herald newsroom and be available for any assignment that popped up. Few ever did. Only a couple of reporters worked Saturday evenings, and we’d usually end up talking to pass the time. One of the Saturday night storytellers was Bill Burrus, the medical writer. Bill had worked for the National Enquirer at one point in his career. The grocery store tabloid was something he didn’t relish talking about. He was a resourceful reporter, however. When Lee Harvey Oswald was shot and brought to Parkland Hospital, where he died in surgery, Burrus happened to be at the hospital and was found hiding behind a curtain outside the trauma room.

Burrus also wrote about Marina Oswald, Lee Harvey’s widow. Her business manager, James Herbert Martin, complained to the Warren Commission that a Burrus piece about Mrs. Oswald was “a very good article and not quite true . . . It embellishes the truth.” Asked for specifics, Martin told the commission that Burrus wrote Mrs. Oswald “continued her studies of the English language and watched television, including her favorite Steve Allen Show.” Said Martin: “She doesn’t even like Steve Allen. And of course she is never studying English. That is the trouble with newspapers. I told Bill Burrus that she watches Steve Allen. She does but just for lack of anything else to do.”

One Saturday, July 23, I was told not to go to police headquarters, but to a neighborhood in south Oak Cliff in the city’s southwest section. As junior reporter, I got to cover the Dallas Soap Box Derby, of which the Times Herald was a sponsor, along with the city’s Chevrolet dealers and the Optimist Club. The derby, begun in 1933 and continuing to this day, has kids racing downhill in motor-less car bodies that today resemble little race cars. But then, the racers were more primitive.

Alas, the Sunday edition’s first deadline occurred before the races concluded. So I phoned in my notes on the early races and racers to another reporter downtown, and he fashioned a story that began: “Saturday was Soap Box Derby Day in Dallas, and with it came hundreds of spectators to watch some 80 youngsters zoom down the new Derby Hill on Kiest Boulevard. To the winner of the annual event went a hefty trophy, a $500 savings bond and a ticket to the All-American Soap Box Derby in Akron, O., Aug. 7.” Of course the story didn’t name the winner because to that point there was no winner.

When the event ended in early evening, I went back to the newspaper and subbed the early story with my own version, which began like this:

Becoming perhaps the most nonplussed winner of Dallas’ Soap Box Derby, sandy-haired Jim Lamb zoomed down Derby Hill five times Saturday to win the annual event over 67 other contending youngsters.

For five minutes—as his fellow racers pushed his car back to the finish line and his mother searched frantically for his father, Charles L. Lamb of 4007 Goodfellow Drive—Jim said not a word.

After he had accepted his trophy, a $500 savings bond, a kiss from 15-year-old Derby queen Susan England and a soft drink from a friend, Jim finally came to life.

“Hey, can I get up now? My back’s getting cramped.”

Yup, I was now a big city newspaper reporter! The truth of it is, I was not the least bit unhappy at this assignment. Soap Box Derby or not, it was a race, wasn’t it? And I was starting, bit by bit, to develop a style of expression that was totally my own. The process would take decades to come to full fruition, but you have to start somewhere.

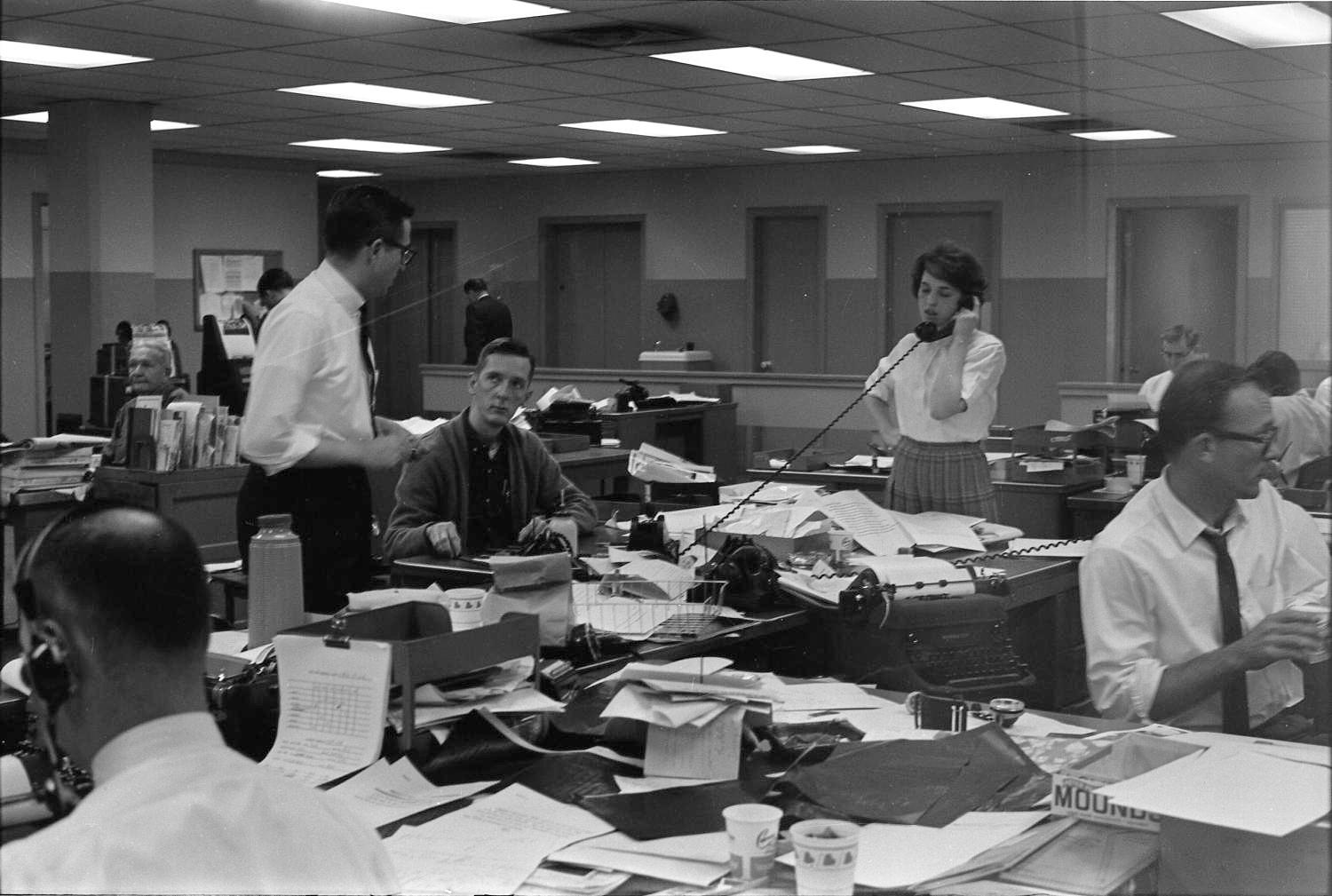

Luck seemed to follow me everywhere in my professional life. In 1987, while at U.S. News & World Report and wishing I weren’t, I was having lunch with the writers whose stories I edited. One of my young writers blurted: “I just turned down the number-three job at Changing Times,” the monthly money magazine later renamed Kiplinger’s Personal Finance. “You what?” I said back, startled. Several months later, I had that job and her to thank for letting me know the opportunity existed. Somewhat the same luck awaited me on June 7, 1965. when I walked out of the elevator into the fourth-floor newsroom of the Dallas Times Herald. I was the newspaper’s summer intern. Who knows how many kids applied for that job? I got it.

Luck seemed to follow me everywhere in my professional life. In 1987, while at U.S. News & World Report and wishing I weren’t, I was having lunch with the writers whose stories I edited. One of my young writers blurted: “I just turned down the number-three job at Changing Times,” the monthly money magazine later renamed Kiplinger’s Personal Finance. “You what?” I said back, startled. Several months later, I had that job and her to thank for letting me know the opportunity existed. Somewhat the same luck awaited me on June 7, 1965. when I walked out of the elevator into the fourth-floor newsroom of the Dallas Times Herald. I was the newspaper’s summer intern. Who knows how many kids applied for that job? I got it.