I didn’t realize when I started covering the labor movement that it came with a huge fringe benefit—a gift that kept on giving, year after year. In fact, if you count the time I spent on this beat at both the Sun-Times and later at U.S. News & World Report, this fringe benefit amounted to ten weeks of warm vacation at a luxury hotel near Miami Beach in the middle of winter, all my expenses paid.

I didn’t realize when I started covering the labor movement that it came with a huge fringe benefit—a gift that kept on giving, year after year. In fact, if you count the time I spent on this beat at both the Sun-Times and later at U.S. News & World Report, this fringe benefit amounted to ten weeks of warm vacation at a luxury hotel near Miami Beach in the middle of winter, all my expenses paid.

I’m talking about the annual pilgrimage of the AFL-CIO Executive Council to the Americana Hotel in Bal Harbour, Fla. The council was made up of almost three dozen presidents of the biggest unions affiliated with the labor federation. They would confer for a week every morning among themselves or with invited guests, privately. Then George Meany, the formidable president of the AFL-CIO, would emerge to brief reporters on what had transpired, react to the news of the day, and answer our questions until we were all exhausted. After that, Meany would gather a few friends and play golf the rest of the afternoon at the Doral Golf Club (later, of course, a Donald Trump property). Even at age 75, he could sometimes score in the low 80s.

Today, decades later, I miss George Meany. Compared to his successors at the AFL-CIO—and if you want to be truthful, to just about everyone else in American life now—he was a giant. Squat and plump, with thick glasses and his ever-present cigar, this former plumber didn’t impress you with his looks. Rather, he led with his integrity. Personally, he was morally incorruptible. He wanted what was best for American working men and women, and would work with either political party to achieve such goals. He was a patriot, too, in the Cold War a staunch anti-Communist who lent the AFL-CIO’s powerful connections with labor unions in western and eastern Europe to the services of his government. Few people realize what a vital role the AFL-CIO quietly played in helping unions behind the Iron Curtain break away from Soviet domination.

So when George Meany spoke, he made news. His utterances were blunt, plain-spoken. Deriding a proposed tax cut by President Richard Nixon in 1969, he said it would hand the Average Joe $50, “which he’ll hand over to the first head waiter he sees.”

My routine at these meetings during 1969-1971 went like this: At the Americana, I’d spend the morning on the beach and the early afternoon writing one, two or even three stories for the next morning’s Sun-Times that arose from Meany’s mid-day briefing. Usually I also snatched interviews all week for a Sunday feature story. Most evenings I and other reporters snared a union president to take to dinner—or a union president snared us. Late-evening entertainment was watching hookers wait for business to develop in the Americana’s crowded bar.

In 1970 in Bal Harbour, my Sunday story resulted from a two-hour interview with Meany—a real coup because he didn’t often sit down with individual reporters. I steered clear of issues of the day. Instead I asked when he’d know it was time to step down. We talked about the health and strength of the labor movement. How effective was the AFL-CIO with Congress?

Of special interest was a split that had developed within labor’s ranks. The United Auto Workers, led by its founder Walter Reuther, had just withdrawn from the AFL-CIO and formed an alliance with the Teamsters Union. Together, the two biggest unions in the country seemed to signal they would form a labor confederation to compete against the AFL-CIO. I asked Meany what he thought.

“This is history repeating itself,” he replied. In 1934, John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers indicted the American Federation of Labor for failing to organize mass-production industries. “I was at the 1934 AFL convention,” Meany said, “and Lewis made quite a showing. He came to the convention in 1935 in Atlantic City, and his strength had grown tremendously. Some of the old-timers said, ‘Give him another year and he’ll be all right’

“But Lewis didn’t want another year. He wanted to split.” Lewis took the UMW out of the AFL and formed the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which in often-violent campaigns swiftly organized the auto, steel, tire, meatpacking and other big industries spurned by the craft-oriented AFL. Three decades passed before the two federations united as the AFL-CIO. Now Meany feared it was happening again. “The formation of the CIO was a shot in the arm to the labor movement. We don’t need a shot in the arm now.”

In fact, the AFL-CIO did need a shot in the arm, but the normally astute Meany failed to recognize that. Organized labor in 1970 was at the height of its power and influence. From that point, it would all be a slow downhill roll. Outside of government and a few key industries, the role of unions today is peripheral.

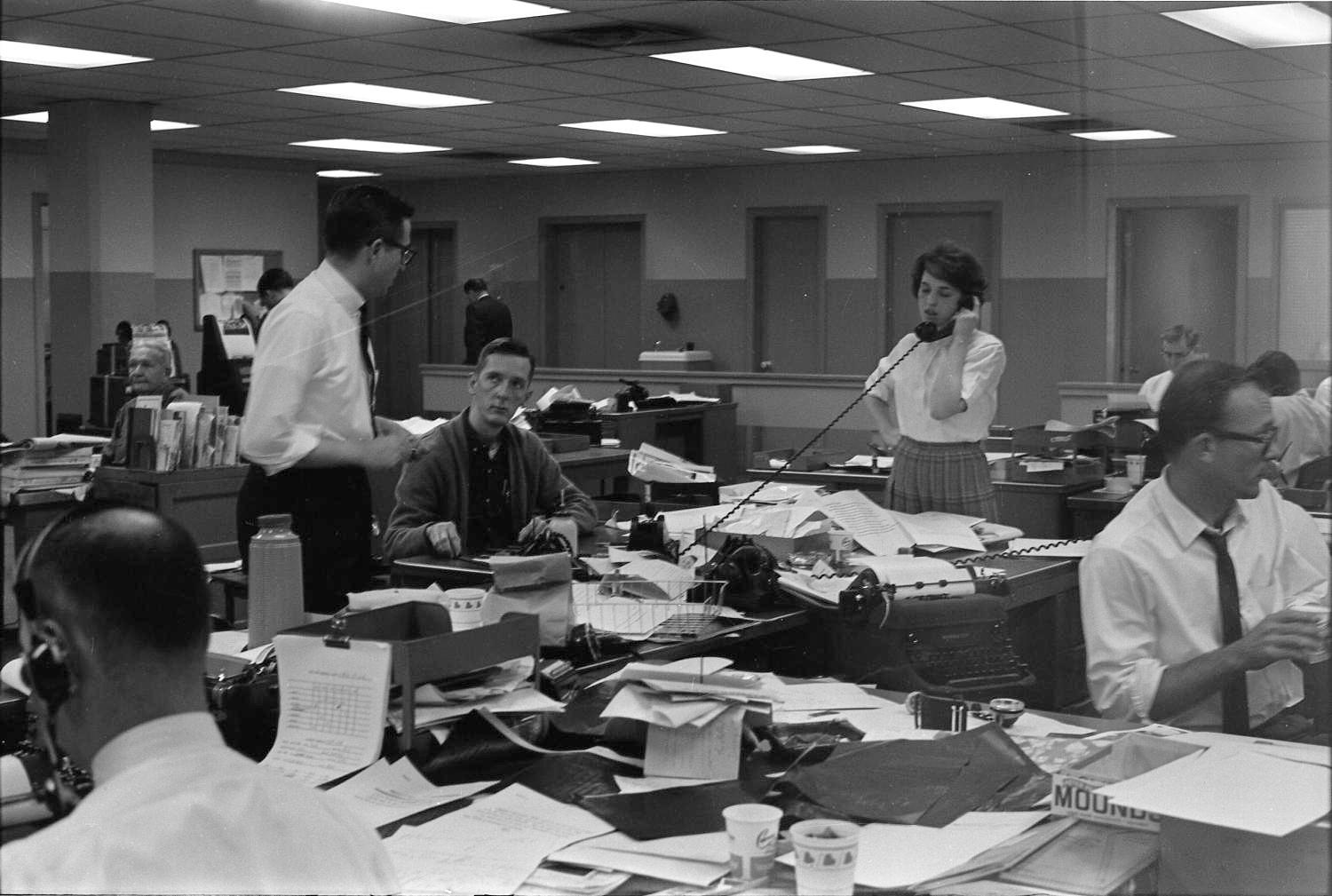

The story I wrote from Bal Harbour for Sunday’s paper as a result of that chat revealed a reflective side of a public figure who seldom let his guard down in public. Emmet Dedmon, the executive editor, came out of his lair when I returned to Chicago to give me a loud attaboy in the city room. Emmet, he of the mighty temper, didn’t do that often.

One more thing about Bal Harbour and those mid-February meetings of the AFL-CIO. In 1974 I would again cover the workplace, this time for U.S. News & World Report newsmagazine. The beauty of working for a weekly publication was that I wrote only one story that week, on whatever theme seemed most appropriate. At U.S. News, I’d go to Florida two weeks instead of one, to also cover meetings of the AFL-CIO building-trades unions. Ultimately, I would secretly report and write my Bal Harbour stories before I even left Washington, D.C., taking them with me to turn in on deadline. You can imagine how relaxing such weeks were for me in Florida. I watched those newspaper and wire service reporters batting out stories all afternoon with wry amusement.