A few chapters ago, in “Jesse Jackson Writes Me a Letter,” I recounted the months of protests and negotiations that culminated, in January of 1970, in an agreement to train 4,000 young blacks as apprentices in the mostly white Chicago building trades unions. The number was a pittance, but at least a start in opening up well-paying jobs to an entire race that had been excluded. To run the job-training project, the unions and civil rights groups agreed upon Fred Hubbard, the handsome, well regarded alderman of the Second Ward, elected in 1967. Hubbard fit the script because he was 1) black, and 2) not a member of Mayor Richard Daley’s machine. But it might be said that the selection of Hubbard as $25,000-a-year administrator of what was called the Chicago Plan became the beginning of Hubbard’s undoing. In accepting the side job, he had in effect been co-opted.

The U.S. Department of Labor made a $450,000 grant to cover administrative costs. But barely a year later, it became clear that the Chicago Plan, if not a sham, had stumbled badly. The Chicago Plan was supposed to prepare young blacks to be channeled into existing union apprenticeship programs and to qualify those with some craft experience for journeyman status in a short time. But in April of 1971 I canvassed the unions and wrote that only 855 positions had been created for blacks in the plan’s first 14 months. Hubbard said a poor construction climate was largely to blame, but added that unions were also dragging their feet. In early May I wrote that the Labor Department was prepared at any moment to declare the Chicago Plan a failure and to impose minority hiring quotas

I submitted my resignation to the Sun-Times on Thursday, May 20. Wouldn’t you know, on Friday May 21 I get a call from Tom Nayder, secretary-treasurer of the Chicago Plan and by then president of the Chicago Buildings Trades Council. He wanted to alert me to an announcement soon to be made. What’s that, I asked? Tom told me and I nearly fell over backward.

The Amalgamated Trust & Savings Bank the previous day had returned a Chicago Plan check for insufficient funds. That’s not possible, Nayder thought–the account has $70,000 in it. A quick audit revealed that some $98,450 was actually missing. The money had been removed by a series of checks made out to Fred Hubbard and signed by Tom Nayder and Arthur O’Neil, a contractor, except that neither Nayder nor O’Neal had ever signed them. The most cursory examination revealed crude forgeries.

The page one story that Saturday, reported by me and court house reporter Tom Moore and written by me, was a bombshell. Alderman Hubbard was nowhere to be found. In fact, he had not been around City Hall to get his mail all week. The hunt was on!

Of course, you can imagine the effect this had on me. I was totally energized, even wondering if I should try to revoke my resignation. Luckily for me, city editor Jim Peneff didn’t bear me a grudge and let me pursue the story the next week, aided primarily by Art Petacque. Decades later, I still count those days working with my hero Art as the high mark of my five years at the paper. Art was a legend when I got there, and the passing years only raised my esteem for him.

Art’s modus operandi was to wheel his desk chair beside yours and say, “Okay, here’s what I know. . . .” I’d feed a sheet of paper into my typewrite and tap out notes as he dictated to me what he’d learned. By Wednesday, May 26, our readers knew that Fred Hubbard was no choir boy. Art discovered his weakness for gambling. He frequented a floating crap game connected to the Chicago Crime Syndicate. He was also well known in the Las Vegas casinos, Art reported, having most recently been seen at Caesar’s Palace on May 14 at a testimonial dinner for the boxer Joe Louis.

On Thursday, May 27, a federal arrest warrant was issued, accusing Hubbard of cashing a forged $20,000 check. I also learned–for the life of me, I don’t remember how–that as recently as the previous Saturday Hubbard had cashed a $1,000 personal check in Las Vegas. The check-cashing service obviously was unaware of the storm that had broken over Hubbard in Chicago the day before.

On Wednesday, June 2, a Cook County grand jury indicted Hubbard and Camille Landry, his 20-year-old mistress (Hubbard was married at the time) on charges of stealing $98,450 from the Chicago Plan. Landry’s role in the crime was not revealed by the indictment. As for Hubbard, I wrote in my next-to-last story for the newspaper that he had contacted another former mistress, living in Redondo Beach, Cal., and she wired him $50 to fly from Las Vegas to Los Angeles on May 25. In LA, she rented Hubbard a Ford Galaxie and he drove away, to places unknown. And in my last piece, published Saturday, June 12, I reported that the Labor Department was officially ending its financial support for the Chicago Plan. So much for lofty goals. Las Vegas trumped social justice.

A few postscripts. For 15 months, Fred Hubbard vanished. Then he was identified in a California poker parlor, arrested, brought back to Chicago, convicted of embezzlement and sentenced to two years in prison. He again drifted out of the public eye, only to be arrested in 1986 for propositioning a 13-year-old girl at a Chicago public school where he taught under the name Andrew Thomas. His disgrace was now complete.

And what of those job opportunities in the Chicago construction trades for young blacks? The Chicago Plan got almost nowhere before Fred Hubbard’s crime led to its demise. The Labor Department never imposed hiring quotas in place of the Chicago Plan, either. Almost a quarter century after the events I’ve just described, very little had changed. The Chicago Tribune reported in 1994 that the big, 5,600-member Carpenters Union local had barely 700 minority-group members. Other unions, such as the Pipefitters, actively tried to drive out its few black journeymen. On the plus side, 20 percent of apprentices of the Plumbers and Electricians unions were black. Clearly, the real victims of Fred Hubbard were the people he purported to help.

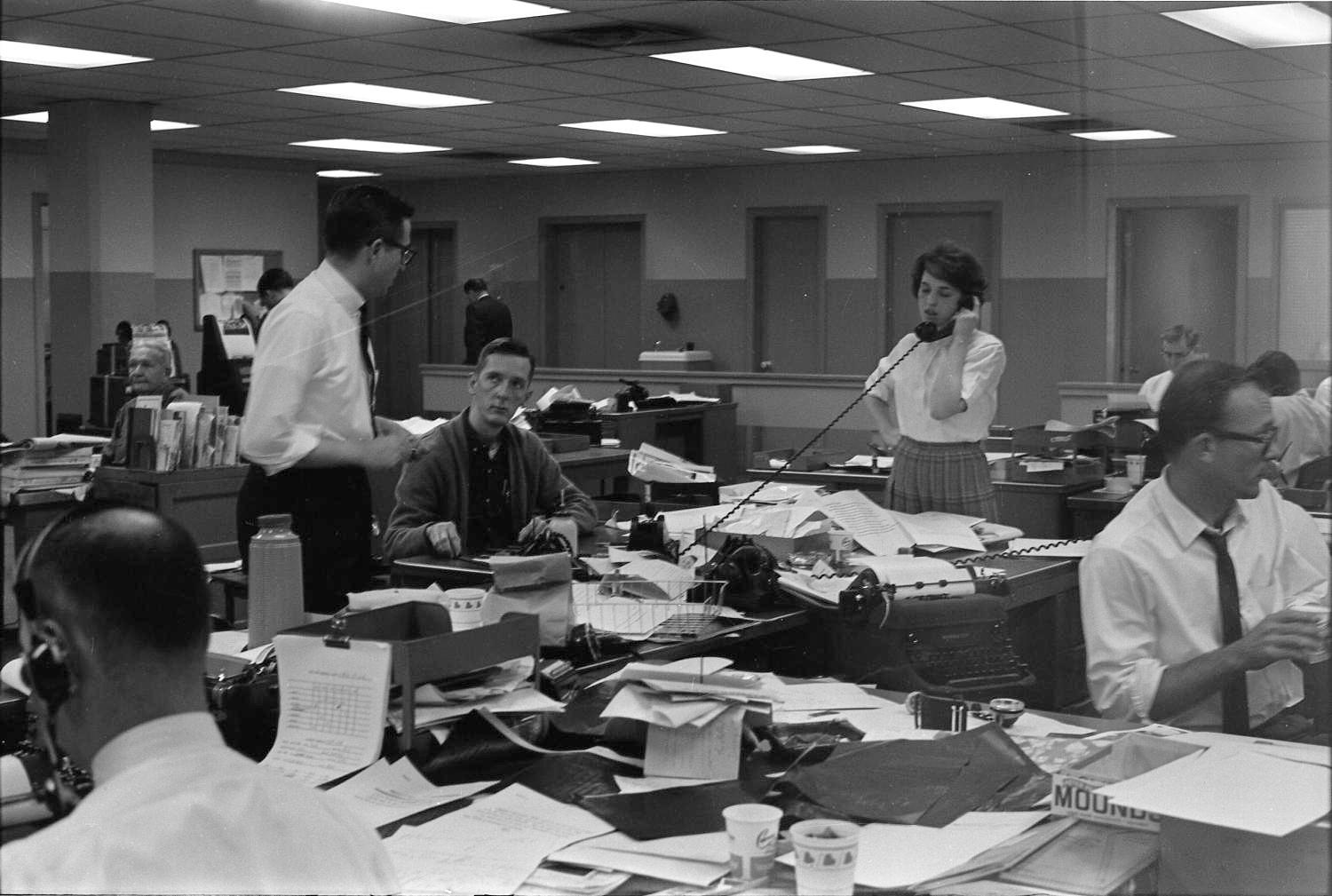

On Friday, June 12, 1971, I gathered my things, said my goodbyes to Art and Jim and John Adam and all the other people in the Sun-Times city room who had become my brothers and sisters and left 401 North Wabash Street for the last time. My newspaper career was over.