On Thursday, June 9, 1966, Dallas McCall, a 17-year-old junior and football player for DeSable High School on the South Side, sat down beside a friend in the school lunchroom. As McCall later explained, the boy seated next to him stuck his finger in Dallas’ food. That precipitated a fight, and got both kids hauled to the office of the football coach, who had intervened to stop the ruckus. Both boys got slapped on the head three times by the coach and then were dismissed.

On Thursday, June 9, 1966, Dallas McCall, a 17-year-old junior and football player for DeSable High School on the South Side, sat down beside a friend in the school lunchroom. As McCall later explained, the boy seated next to him stuck his finger in Dallas’ food. That precipitated a fight, and got both kids hauled to the office of the football coach, who had intervened to stop the ruckus. Both boys got slapped on the head three times by the coach and then were dismissed.

Six days later, Dallas McCall underwent surgery at County Hospital for repair of a punctured left eardrum. And the next morning Jim Peneff, the day assistant city editor, handed me a brief notice of the event distributed by City News Bureau and told me to develop a story.

By phone, I talked to the boy’s sister Chinetha and his mother Lula, who blamed the boy’s injury on the cuffing by the coach, Robert Bonner. I also spoke with Bonner, who admitted the slapping but denied it was severe enough to cause injury. Bonner said the boy had been disciplined four times in the past, and explained that’s why the incident went unreported to the school principal—he feared McCall would be suspended. Bonner speculated that McCall may have been hurt by food or dishes thrown during the fight. The DuSable principal wouldn’t return my calls. I wrote about 700 words and turned the story in.

Two things happened as a result. I’d bet my life that after reading this story, personal-injury attorneys began calling Lula McCall to propose she sue the Chicago public schools. And Fred Frailey got his first byline in the Chicago Sun-Times, in the Friday, June 17 edition. My story appeared above advertisements for wigs and briar pipes.

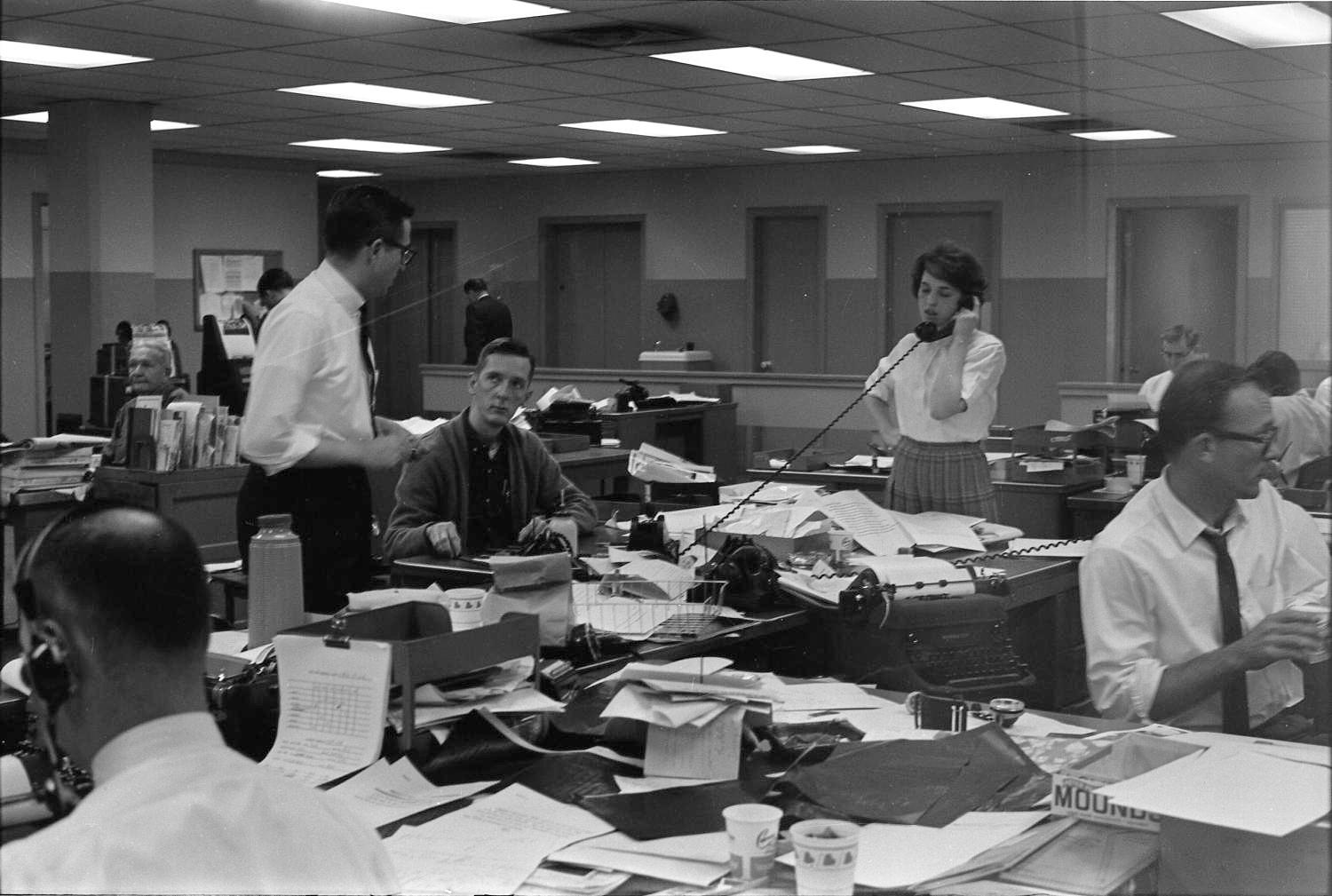

This happened at the conclusion of my second week at the paper. Jim Hoge, the city editor, hired some top-drawer reporters about the time I came along—people like David Murray from the New York Herald-Tribune and Harry Golden Jr. from the Detroit Free Press. These were guys who could walk in on Day One and handle anything you threw at them. And that’s exactly what Hoge liked to do. I recall his putting Murray to work immediately on some big think piece for the Sunday paper. I called such articles “Whither Chicago?” stories because while they were long and serious pieces, they usually provided few answers but merely posed more questions.

And then there were the Fred Fraileys, promising young men and women with relatively little experience, on whom Hoge decided to take a chance. I would write my share of “Whither Chicago?” pieces eventually. But first I had to grow up, so to speak. After those two weeks at the main offices at 401 North Wabash Street, just across the Chicago River from the Loop, I was sent to staff the newspaper’s northwest suburban bureau, in Mount Prospect, 20 miles distant.

I didn’t mind being exiled to the suburbs. I probably had more experience writing stories than 99 percent of the nation’s other journalism school graduates in 1966. But that didn’t mean I was seasoned and ready to tackle complex stories or that I could write with verve and a sense of style. Those things might come in time, but first I needed experience. I considered myself lucky just to be a Sun-Times suburban reporter and was proud to tell new acquaintances what I did for a living.