If you’ve gotten this far, you know me as a 27-year-old newspaper dropout. That was almost half a century ago. What happened next? This is the rest of my story.

U. S. News & World Report, to whose Chicago bureau I reported on June 14, 1971, seemed like an empty refrigerator—substantial only on the outside. There were capable writers and editors, but also a lot of deadwood. The impression I got was that everyone was waiting for David Lawrence, its founder, to retire or pass on. Until then, it seemed that not much would change, and this turned out to be the case. (Lawrence died at age 84 in Sarasota in February 1973.)

My associate in the Chicago office, Peggy Schmidt, was even younger than me and proved quite a capable reporter and writer. The magazine wasn’t much interested in breaking news in our Midwest region or anywhere else. Rather, the emphasis was on “trend” stories. I’ll describe two perennials.

One of the senior editors in Washington, Grant Salisbury, must have grown up a farm boy, because it fell upon him twice a year to craft a feature story on the state of farming in America. This Grant did without ever leaving D.C., relying on a bevy of his own sources and field reporting from the Chicago, Detroit and Houston bureaus. In fact, my first out-of-town assignment was to interview farmers in central Illinois.

To find knowledgeable farmers, I called the director of the Illinois Agricultural Extension Service and asked the name of his most capable and industrious county agent in that part of the state. Then I called that county agent and flattered him with his boss’s compliments. He agreed to spend two days introducing me to farmers he worked with. This I did six times in the next three years, from Illinois to Nebraska, always with great success. It sure beat cold-calling on suspicious strangers in a farm field.

On that first farm assignment, I peppered the county agent with questions as we drove around. I didn’t know the first thing about the business of growing crops or raising livestock, but at least I was curious. From our car, I kept noticing what looked like fields of stunted corn crops. What a shame, I finally said to the county agent. “Son,” he replied, “those are very healthy soybeans.” We both laughed, and I started asking about the economics of raising soybeans.

The other assignment I could count on was the brainchild of the magazine’s resident intellectual, senior editor George Jones. George took upon himself a near-impossible task, crafting every six months a feature story called “Mood of America.” His legmen for this story became the dozen or so correspondents stationed across the U.S. I would set aside a week to wander around the Midwest, approaching strangers on sidewalks and inside taverns, introducing myself and asking what was on their minds about the state of affairs in our nation, the good and the bad. Amazingly, I got close to 100 percent cooperation from those I accosted, and in that week, themes always seemed to emerge. I’d write a long file for George my first day back, full of my impressions—and dozens of direct quotes—and wait to see how much of what I sent him ended up in the published piece.

I wonder today how much George Jones had to struggle to make his latest “Mood of America” article different from the ones before it. About the fifth or sixth time of working this story, I got bored. I called the Detroit bureau chief and proposed we make a bet: Whoever got the strangest name of a town we visited into George’s finished story would be taken to dinner by the other. That time I was supposed to wander through South Dakota, Minnesota and Iowa, so I studied the names of little towns on the state maps, and in a matter of minutes knew I had a plan. In fact, I flew to Sioux City and beelined to Buffalo Trading Post, S.D., interviewing everyone I could find in that sleepy crossroads. And my last stop of the week-long trip was What Cheer, Iowa. The sidewalks were empty, but I struck gold in the town’s only bar, where people on the stools thought it hilarious that someone would want to know what they thought. I won hands down.

But the truth is that you can only travel so much. Most of the time I worked stories by phone from Chicago’s Prudential Building. Few were pieces I did all on my own; the clear majority were “roundup” articles that all the bureaus contributed to and someone in Washington wrote. I missed both newspapers and the labor beat. Learning of a vacancy in the Chicago office of the Los Angeles Times, I wrote its national editor, to no avail.

Sometimes you catch a break by just waiting patiently, and mine arrived in 1974. Archie Robinson, the magazine’s labor writer since the late 1940s, beloved by everyone on the magazine staff and by the labor union chieftains he wrote about, announced his retirement as of August. My boss, David Richardson, the chief of correspondents, put in a good word with the new managing editor, Marvin Stone, and in August, as newspaper front pages announced the resignation of Richard Nixon, Maggie and I and two-year-old daughter Barbara moved to Washington. Our son Will was born that November.

Writing about unions and the workplace—every week of the year—was as satisfying a job as I ever had. I was, in effect, my own boss, thinking up my own stories, doing my own reporting and writing my own articles. It helped that I had a kindly editor, Ellis Haller, and that Marvin Stone was energizing the magazine with new people and fresh ideas. Well, not always fresh ideas. Marvin had a habit of tearing stories out of old U. S. News issues and sending them to writers with the words, “Time to do again.” For some reason, this irritated me. When I’d suffered enough, I told Marvin I came up with better ideas than these old chestnuts. “That may be,” Margin replied, “but these were good ideas, too, and we didn’t do them well. I’m challenging you to make them sparkle.” That shut me up.

I kept that assignment four years, learning how to craft a magazine article (quite different from a newspaper story), traveling frequently around the country (always by train, when I could) and reveling in the company of both union leaders and working men and women. And by the way, filling two or more pages of every issue of the magazine made me the most productive writer on the staff. Raises came easily.

By 1979 I was deemed ready to become an editor, starting with editing my successor on the labor beat, Sara Fritz, who I lured away from the same job at United Press International. Let me just say of editing that it pays well. But if you want job satisfaction, stay a reporter and writer.

It took 30 years before I returned to being a writer. In the interim, as an assistant managing editor at U. S. News, I ended editing up its business coverage. But with the purchase of this employee-own magazine by the developer Mort Zuckerman in 1985 came a realization: If you worked there when Mort came to rescue it (in his mind) from certain oblivion, you didn’t deserve a promotion, and none of us got one. I liked Zuckerman as a person, but I didn’t like what looked like a dead end. I got out of there in 1987, to become deputy editor of Changing Times, which several years later became Kiplinger’s Personal Finance Magazine. The last eight of my 22 years there were as its editor.

So now, at age 74, I am a writer again. My platform is Trains, a magazine about railroads and railroaders. I wrote my first story for Trains in 1978—10,000 words, every one of which was published!—and have continued to freelance for the monthly publication. I told its editor, Jim Wrinn, when I retired from Kiplinger’s Personal Finance in 2009: “I’m yours. Milk me like a dairy cow until I drop.” That he has done.

Now you know the rest of my story. Two marriages, five children and now grandchildren—I’ve been fortunate. But the times in life I still dream about are those newspaper days. I was young, burning with ambition, eager to live the life, which I assuredly did. I wouldn’t trade those 11 years for anything.

I don’t think many of my Sun-Times colleagues realized what a great job I had covering labor unions. They probably considered the beat to be boring. So did I, before I was offered it and discovered what a mother lode of stories flowed from unions and their clashes with both managements and each other. Think of contract talks as you might think of negotiations between opposing armies. And think of a strike or lockout as economic warfare. Does that whet your interest? My job was to keep score and explain what was happening. Never was I more challenged than during the 85-day trucking strike and lockout of 1970.

I don’t think many of my Sun-Times colleagues realized what a great job I had covering labor unions. They probably considered the beat to be boring. So did I, before I was offered it and discovered what a mother lode of stories flowed from unions and their clashes with both managements and each other. Think of contract talks as you might think of negotiations between opposing armies. And think of a strike or lockout as economic warfare. Does that whet your interest? My job was to keep score and explain what was happening. Never was I more challenged than during the 85-day trucking strike and lockout of 1970. All wars end, eventually. This conflict became a war of attrition. Six weeks into it, I wrote that thousands of idled Teamsters had applied for food stamps. But it was the employers who finally ran up the white flag. On June 2, the two sides agreed upon a $1.65-an-hour settlement spread across three years, a nickel less than what the Teamsters had sought when the fireworks started. So great was the influence of this settlement that the Teamsters’ national leadership said its pending agreement for over-the-road truckers would be amended to match what the Chicago Teamsters achieved.

All wars end, eventually. This conflict became a war of attrition. Six weeks into it, I wrote that thousands of idled Teamsters had applied for food stamps. But it was the employers who finally ran up the white flag. On June 2, the two sides agreed upon a $1.65-an-hour settlement spread across three years, a nickel less than what the Teamsters had sought when the fireworks started. So great was the influence of this settlement that the Teamsters’ national leadership said its pending agreement for over-the-road truckers would be amended to match what the Chicago Teamsters achieved. Every so often the entertainment world tries to put on a newspaper drama that grabs peoples’ attention. Those efforts almost always fail. The stories reporters write may be fascinating, but the process of producing them is not. Interviews are usually dull affairs unless you’re a participant. And how do you dramatize the thinking process as a story is written or edited?

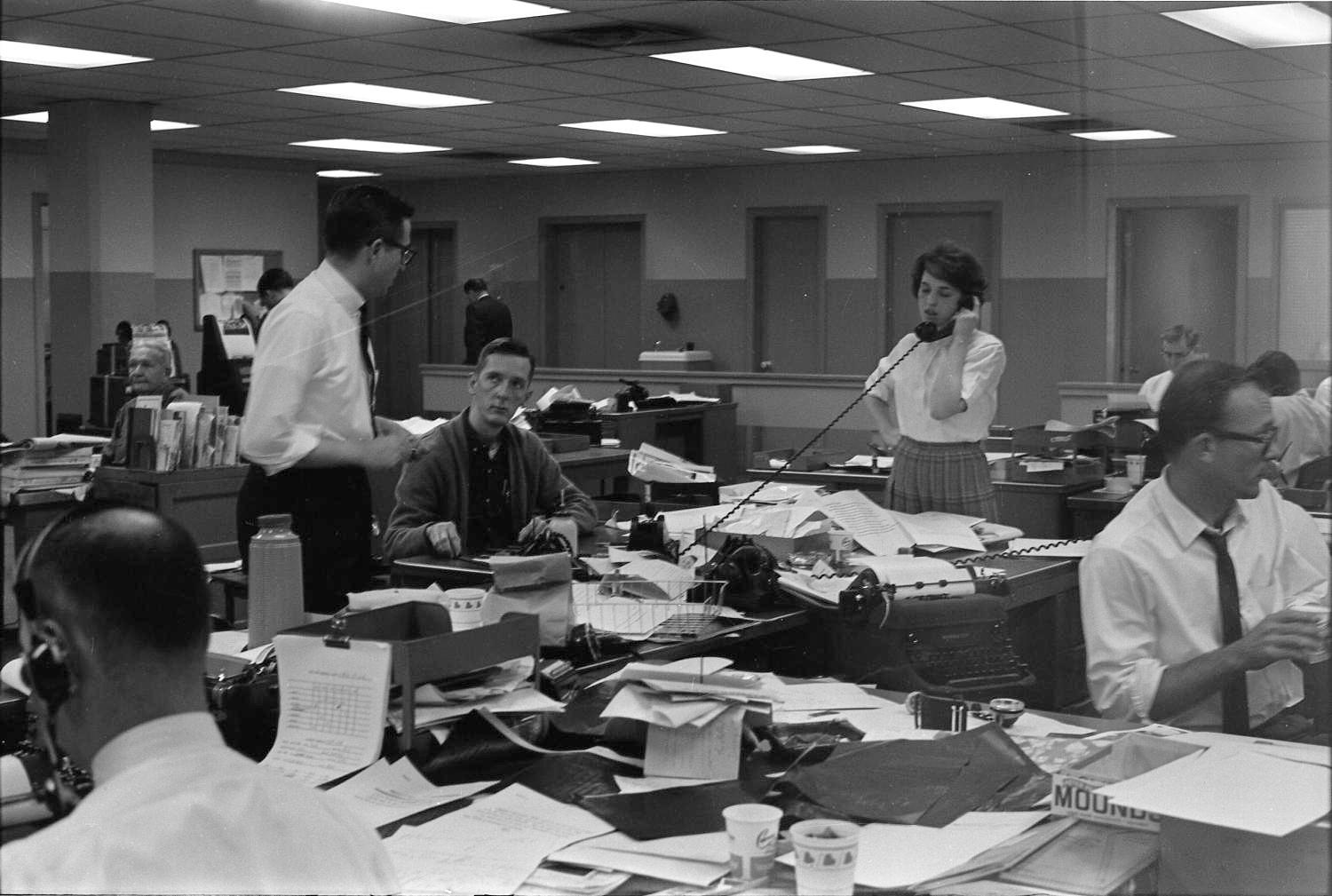

Every so often the entertainment world tries to put on a newspaper drama that grabs peoples’ attention. Those efforts almost always fail. The stories reporters write may be fascinating, but the process of producing them is not. Interviews are usually dull affairs unless you’re a participant. And how do you dramatize the thinking process as a story is written or edited? When I showed up for work the morning of Tuesday, March 3, 1970, Leighton McLaughlin, the day assistant city editor, leapt to greet me as if I were his long-lost son. Thank goodness, he was smiling. I’d been in Pittsburgh the day before at a United Steelworkers event and, being who I was, took an overnight train back to Chicago, then went directly to work. “We tried to find you last night,” Mac said, but this was decades before cell phones. Then he laid an amazing story at my feet.

When I showed up for work the morning of Tuesday, March 3, 1970, Leighton McLaughlin, the day assistant city editor, leapt to greet me as if I were his long-lost son. Thank goodness, he was smiling. I’d been in Pittsburgh the day before at a United Steelworkers event and, being who I was, took an overnight train back to Chicago, then went directly to work. “We tried to find you last night,” Mac said, but this was decades before cell phones. Then he laid an amazing story at my feet. The union organizer. For the paper’s Sunday magazine of June 15, 1969, I profiled a union’s effort to win bargaining rights for employees of a hospital in suburban Oak Park. The organizer was Harry Kurshenbaum, who agreed to let me be his shadow during a months-long campaign to win over the hospital’s workers. It was an ambitious effort by me at what is today called “long form journalism” and what I think of as simply good magazine writing. Happily, it worked, although not for Harry Kurshenbaum. The story begins:

The union organizer. For the paper’s Sunday magazine of June 15, 1969, I profiled a union’s effort to win bargaining rights for employees of a hospital in suburban Oak Park. The organizer was Harry Kurshenbaum, who agreed to let me be his shadow during a months-long campaign to win over the hospital’s workers. It was an ambitious effort by me at what is today called “long form journalism” and what I think of as simply good magazine writing. Happily, it worked, although not for Harry Kurshenbaum. The story begins: Death at 100 mph. The morning of Friday, January 17, 1969, began cold and overcast. Over the radio came news of a head-on collision just after midnight between two Illinois Central trains 50 miles south of Chicago—one a passenger train, The Campus, doing 100 mph. Three crew members died, including both locomotive engineers. I called the city desk from our apartment and got permission to go to the accident site, in hopes of figuring out what really happened.

Death at 100 mph. The morning of Friday, January 17, 1969, began cold and overcast. Over the radio came news of a head-on collision just after midnight between two Illinois Central trains 50 miles south of Chicago—one a passenger train, The Campus, doing 100 mph. Three crew members died, including both locomotive engineers. I called the city desk from our apartment and got permission to go to the accident site, in hopes of figuring out what really happened. In July of 1969, 17 black youths seized the offices of the Chicago Building Trades Council, the federation of construction unions, to demand that high-paying construction jobs be opened up to African-Americans. It was the start of an uprising that would shake the city’s most politically powerful unions for months. The building trades were unions whose apprenticeships were handed down by fathers to sons, or by uncles to nephews, and nonwhites need not apply. For example, in 1969 blacks constituted just 6 percent of the apprentices in 12 construction unions and only 3 percent of the journeyman members.

In July of 1969, 17 black youths seized the offices of the Chicago Building Trades Council, the federation of construction unions, to demand that high-paying construction jobs be opened up to African-Americans. It was the start of an uprising that would shake the city’s most politically powerful unions for months. The building trades were unions whose apprenticeships were handed down by fathers to sons, or by uncles to nephews, and nonwhites need not apply. For example, in 1969 blacks constituted just 6 percent of the apprentices in 12 construction unions and only 3 percent of the journeyman members. That night, at home, I gave myself a pat on the back. I was in the midst of a big melee—a mini-riot—and had kept my cool. When the first edition deadline had approached, I found a pay phone, told the rewrite man I’d dictate the complete story from top to bottom and did just that, propping the phone against my shoulder as I consulted my notes. Any reporter will tell you that composing a news story on the phone is an acquired skill, and at age 25 I had acquired it.

That night, at home, I gave myself a pat on the back. I was in the midst of a big melee—a mini-riot—and had kept my cool. When the first edition deadline had approached, I found a pay phone, told the rewrite man I’d dictate the complete story from top to bottom and did just that, propping the phone against my shoulder as I consulted my notes. Any reporter will tell you that composing a news story on the phone is an acquired skill, and at age 25 I had acquired it. At 3:35 p.m. that afternoon, after the first edition deadlines of both morning papers, I called “Jimmy Hoffa”—Jim Strong—at the Tribune. Here’s what the Sun-Times will publish, I said, for once stealing a beat on my dear friend and chief rival. When the One-Star Edition came up at 5 o’clock, my story was on the top of Page One. And best of all, it carried a 20-point tag line that warms any reporter’s heart: EXCLUSIVE.

At 3:35 p.m. that afternoon, after the first edition deadlines of both morning papers, I called “Jimmy Hoffa”—Jim Strong—at the Tribune. Here’s what the Sun-Times will publish, I said, for once stealing a beat on my dear friend and chief rival. When the One-Star Edition came up at 5 o’clock, my story was on the top of Page One. And best of all, it carried a 20-point tag line that warms any reporter’s heart: EXCLUSIVE. I didn’t realize when I started covering the labor movement that it came with a huge fringe benefit—a gift that kept on giving, year after year. In fact, if you count the time I spent on this beat at both the Sun-Times and later at U.S. News & World Report, this fringe benefit amounted to ten weeks of warm vacation at a luxury hotel near Miami Beach in the middle of winter, all my expenses paid.

I didn’t realize when I started covering the labor movement that it came with a huge fringe benefit—a gift that kept on giving, year after year. In fact, if you count the time I spent on this beat at both the Sun-Times and later at U.S. News & World Report, this fringe benefit amounted to ten weeks of warm vacation at a luxury hotel near Miami Beach in the middle of winter, all my expenses paid. When I joined the Sun-Times, it was an article of faith on my part that, given time, my newspaper could overtake and eclipse the mighty Chicago Tribune. The Trib was “caught in a time warp,” as it later admitted on its own pages. Colonel Robert Rutherford McCormick, known as The Colonel (or just Bertie to his family) had ruled the Tribune Company for almost half a century before his death on April 1, 1955. He was staunchly conservative, and the news columns of the Tribune plainly reflected McCormick’s partisanship.

When I joined the Sun-Times, it was an article of faith on my part that, given time, my newspaper could overtake and eclipse the mighty Chicago Tribune. The Trib was “caught in a time warp,” as it later admitted on its own pages. Colonel Robert Rutherford McCormick, known as The Colonel (or just Bertie to his family) had ruled the Tribune Company for almost half a century before his death on April 1, 1955. He was staunchly conservative, and the news columns of the Tribune plainly reflected McCormick’s partisanship.

Steam locomotive 844 and I entered this world months apart in 1944. The last steam locomotive built for Union Pacific, it never left that railroad’s active roster. Instead, it has served for half a century as UP’s good-will ambassador. With its 80-inch driving wheels, it is a magnificent machine that impresses people of all ages. Yesterday, Cathie and I rode behind the 844 from Denver to Cheyenne and back aboard the train the Denver Post and UP sponsor to celebrate Frontier Days in Cheyenne and benefit Colorado charities. We had seats in the dome of the coach named “Challenger.” My thanks to Chip Paquelet for giving hard-to-get tickets he couldn’t use to Dick Strong, and to Dick and Donna Strong for thinking of us.

Steam locomotive 844 and I entered this world months apart in 1944. The last steam locomotive built for Union Pacific, it never left that railroad’s active roster. Instead, it has served for half a century as UP’s good-will ambassador. With its 80-inch driving wheels, it is a magnificent machine that impresses people of all ages. Yesterday, Cathie and I rode behind the 844 from Denver to Cheyenne and back aboard the train the Denver Post and UP sponsor to celebrate Frontier Days in Cheyenne and benefit Colorado charities. We had seats in the dome of the coach named “Challenger.” My thanks to Chip Paquelet for giving hard-to-get tickets he couldn’t use to Dick Strong, and to Dick and Donna Strong for thinking of us.

LOUISVILLE — A railroad with century-old roots in Indiana ran its last regularly scheduled passenger train Saturday. The last runs of No. 5 and 6, the Louisville-to Chicago Thoroughbred on the Monon R.R., had something of a funeral flavor.

LOUISVILLE — A railroad with century-old roots in Indiana ran its last regularly scheduled passenger train Saturday. The last runs of No. 5 and 6, the Louisville-to Chicago Thoroughbred on the Monon R.R., had something of a funeral flavor. January 13: A Toast: 631 Club on the Rocks

January 13: A Toast: 631 Club on the Rocks This concerned a tabby named Tiger Paws who had been adopted by the maintenance workers at the “Zephyr Pit,” where Burlington Lines passenger trains were serviced just north of Roosevelt Road. The cat jumped aboard trains for a ride one too many times and was lost. My story reported that someone had found a haggard cat resembling Tiger Paws near the railroad not far from Aurora. But nobody from the railroad bothered to go out and retrieve the animal. My story concluded: “Too bad for you, Tiger Paws. Or whoever you are.”

This concerned a tabby named Tiger Paws who had been adopted by the maintenance workers at the “Zephyr Pit,” where Burlington Lines passenger trains were serviced just north of Roosevelt Road. The cat jumped aboard trains for a ride one too many times and was lost. My story reported that someone had found a haggard cat resembling Tiger Paws near the railroad not far from Aurora. But nobody from the railroad bothered to go out and retrieve the animal. My story concluded: “Too bad for you, Tiger Paws. Or whoever you are.”

On April 5, 1968, the morning after Martin Luther King’s assassination, Chicago was as tense as a piano wire. Jim Casey, normally stationed at police headquarters for the Sun-Times, was touring the West Side in a patrol car. I was called in from Mount Prospect to stand in for him downtown. I had never been to Chicago police headquarters or its press room, and knew not the first thing to do about reporting what police knew about the rapidly decaying state of safety in the city. Reporters from the other newspapers and broadcast stations were too busy to help me, too. Do you ever have dreams in which you try to accomplish something and can’t seem to get it done? That was me. At 4 o’clock, just after the first edition deadline, Jim Peneff phoned from the city desk to say the governor had activated the National Guard. That night found me in a truck, patrolling the streets of the South Side in company with Chicago police cruisers. That was Friday.

On April 5, 1968, the morning after Martin Luther King’s assassination, Chicago was as tense as a piano wire. Jim Casey, normally stationed at police headquarters for the Sun-Times, was touring the West Side in a patrol car. I was called in from Mount Prospect to stand in for him downtown. I had never been to Chicago police headquarters or its press room, and knew not the first thing to do about reporting what police knew about the rapidly decaying state of safety in the city. Reporters from the other newspapers and broadcast stations were too busy to help me, too. Do you ever have dreams in which you try to accomplish something and can’t seem to get it done? That was me. At 4 o’clock, just after the first edition deadline, Jim Peneff phoned from the city desk to say the governor had activated the National Guard. That night found me in a truck, patrolling the streets of the South Side in company with Chicago police cruisers. That was Friday. So that’s what I did. “Dear Margaret,” it began, and it told of my experiences in uniform the past two days. It consumed all of page 40 in Monday’s paper, with me pictured in helmet and an M16 slung over my shoulder. It was hokey, I admit, but served the purpose of telling readers what it was like to be a soldier in a riotous city. And it calmed my frustration at not being able to practice my writer’s craft.

So that’s what I did. “Dear Margaret,” it began, and it told of my experiences in uniform the past two days. It consumed all of page 40 in Monday’s paper, with me pictured in helmet and an M16 slung over my shoulder. It was hokey, I admit, but served the purpose of telling readers what it was like to be a soldier in a riotous city. And it calmed my frustration at not being able to practice my writer’s craft. My fellow reporter during the late 1960s, John Adam Moreau, said flatly the other day that everyone he knew at the newspaper then who was over age 50 had a drinking problem. That would certainly apply to Ray Brennan (pictured exhaling tobacco smoke at left). Legend has it Ray once disappeared from the city room for more than a year. Then one day he reappeared, sat down at his desk and began making phone calls. “Where you been, Ray?” someone asked. All Brennan said was, “The bridge was up.” John Adam once asked Ray if this story were true. “I won’t deny it,” Ray responded.

My fellow reporter during the late 1960s, John Adam Moreau, said flatly the other day that everyone he knew at the newspaper then who was over age 50 had a drinking problem. That would certainly apply to Ray Brennan (pictured exhaling tobacco smoke at left). Legend has it Ray once disappeared from the city room for more than a year. Then one day he reappeared, sat down at his desk and began making phone calls. “Where you been, Ray?” someone asked. All Brennan said was, “The bridge was up.” John Adam once asked Ray if this story were true. “I won’t deny it,” Ray responded. Ray wasn’t afraid to get to know gangsters. His most notorious association was with Roger Touhy, who made a fortune as a Chicago bootlegger during Prohibition, in the process becoming a rival of Al Capone. Touhy was convicted in 1934 of the kidnapping of John (Jake the Barber) Factor, brother of cosmetics kingpin Max Factor, Sr. However, there was also evidence that Capone had done the kidnapping as a way to implicate Touhy and get him out of the picture.

Ray wasn’t afraid to get to know gangsters. His most notorious association was with Roger Touhy, who made a fortune as a Chicago bootlegger during Prohibition, in the process becoming a rival of Al Capone. Touhy was convicted in 1934 of the kidnapping of John (Jake the Barber) Factor, brother of cosmetics kingpin Max Factor, Sr. However, there was also evidence that Capone had done the kidnapping as a way to implicate Touhy and get him out of the picture. Three weeks later, Brennan and Touhy met for dinner at the Chicago Press Club. They discussed a lawsuit filed against Touhy by Max Factor. Then the men parted and Touhy returned home. On his front steps, he was gunned down and died soon thereafter.

Three weeks later, Brennan and Touhy met for dinner at the Chicago Press Club. They discussed a lawsuit filed against Touhy by Max Factor. Then the men parted and Touhy returned home. On his front steps, he was gunned down and died soon thereafter.